Between 1991 and 2001, Japan went through a 10-year-long period of economic stagnation and price deflation known as Japan’s “Lost Decade”. At the time, pundits were questioning whether or not the U.S. economy would suffer the same fate.

Japan’s Lost Decade is now nearly 30 years long. So far, the U.S. appears to have avoided the same economic catastrophe that Japan created.

Japan was supposed to be the most dominant economy in the world

In the 1980s Japan appeared to be unstoppable. Real estate prices soared in the U.S. as Japanese companies, financial institutions, and investors bought nearly $300 billion of high-profile properties like the Pebble Beach Golf Club and Rockefeller Center.

In a Harvard Business Review article, “What We Can Learn from Japanese Management”, Peter F. Drucker explained why businessmen in the U.S. should view Japan not only as a supplier, customer, and competitor, but also as a teacher. Many Americans and Japanese believed that the writing was on the wall for the U.S.

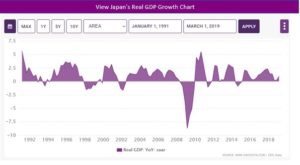

Throughout the 1980s, Japan’s GDP grew at an annual average rate of nearly 4%, compared to just over 3% in the U.S. But then, beginning in 1991, GDP growth in Japan plummeted to about 1.14% annually. As the chart below illustrates, GDP growth in Japan has been anything but predictable:

While the U.S. and Japan attempt to manage their respective economies in slightly different ways, the steps taken are very similar to one another:

Buying government debt

Last November, Japan was the first country in the G7 whose central bank’s balance sheet exceeded the entire GDP of the country. In addition to government debt, the Bank of Japan also owns about 80% of all ETF assets in the country’s stock market, according to the Financial Times.

By comparison, the Federal Reserve currently holds about $2.1 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities, or about 10% of the nation’s $21.06 trillion GDP. While the U.S. central bank has begun unwinding, Bloomberg notes that the Fed will change its plans if the balance sheet wind down began to have a negative affect on the economy.

However, Bloomberg expects the Fed to turn to interest rate tools before it begins buying Treasuries again. Which is exactly what happened last week.

Interest rates

Japan has had a zero-interest rate policy since 1999. The country’s short-term rate sits at -0.1% while 10-year government bond yields are around 0%.

With last week’s rate cut of 0.25%, the Fed is now targeting an interest rate range of between 2% and 2.5%. So, the U.S. doesn’t yet have negative interest rates . . . or does it?

According to the most recent data from the BLS, the June CPI reached 1.6% year-over-year, and 2.1% when food and energy are excluded from the calculation. That’s pretty darn close to a negative net interest rate.

Once people have been trained to expect low rates, they simply stop buying and investing until rates return to the expected ‘norm’. That’s been true for 30 years in Japan, and for over 10 years in the U.S. When the Fed even talks about increasing rates, the markets shudder.

Structural characteristics of Japan’s economy vs. the U.S.

In addition to quantitative easing and low interest rate policies, the economic structures of Japan and the U.S. are similar, though in slightly different ways:

#1 Keiretsu is an intentional structure of dependent relationships between manufacturers, suppliers, and distributors. In Japan, foreign direct investment is discouraged, and free market forces are reduced. The U.S. doesn’t have Keiretsu, but it does have ongoing trade wars that are having the same result.

#2 Guaranteed lifetime employment in Japan was once the norm. Today, only about 8% of Japanese firms offer it, but there are still around 25 million workers who benefit while they wait to reach retirement age. The U.S. doesn’t yet have guaranteed incomes. However, anti-business legislation such as rent control laws on both coasts accomplish something similar, just in a different way.

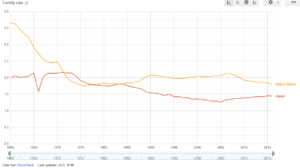

#3 Japan’s population is getting older and fewer babies are getting made. The birthrate in Japan has fallen to the lowest level in history. If this trend continues, the Japan Times predicts that by 2065 Japan will have lost 30% of its population. Back in the 1960s, the U.S. had a fertility rate nearly twice that of Japan’s. Today, baby production in both countries isn’t that far apart:

Japan has been trying to stimulate growth and inflation for 20 years longer than the U.S., but still has nothing to show for it; something the Fed is trying to avoid.